My AI Work

2025-10-29

Back near the end of 2024, I was put into a team with a less traditional focus for government: AI. The purpose of this team wasn't incredibly clear to me. The project they had been working on for the last several months would never see a production-level deployment. It was simply an experiment to see what we could do locally with AI-enabled services and to upskill ourselves with AI knowledge for future projects.

It wasn't really a topic that I was excited for, but I knew this would be a good opportunity to learn valuable skills. I'd like to share some of these learnings, although it's mostly going to be high-level to fit it all in here.

Understanding RAG

A basic Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) system was already in place when I joined. This was my first step to learning how the systems around AI models worked.

In simple terms, RAG is the process of retrieving relevant context from a source, often a database, then providing that to the Large Language Model (LLM) for it to generate an informed response. It's essential that this context contains the necessary information for the LLM regarding whatever question the user is asking.

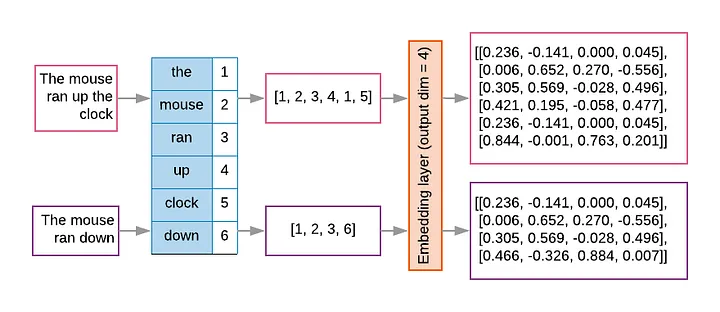

Let's start from the beginning. A user might ask a simple question: “How many days of notice does my landlord have to give in order to evict?” In order to find relevant information, this phrase first has to be broken down into tokens, numbers that represent the parts of the phrase. Each token might be a word, part of a word, or even punctuation. This list of tokens can now be converted into embeddings, a multi-dimensional matrix of float values that represent not just the words but their placement and (hopefully) semantic value in the phrase.

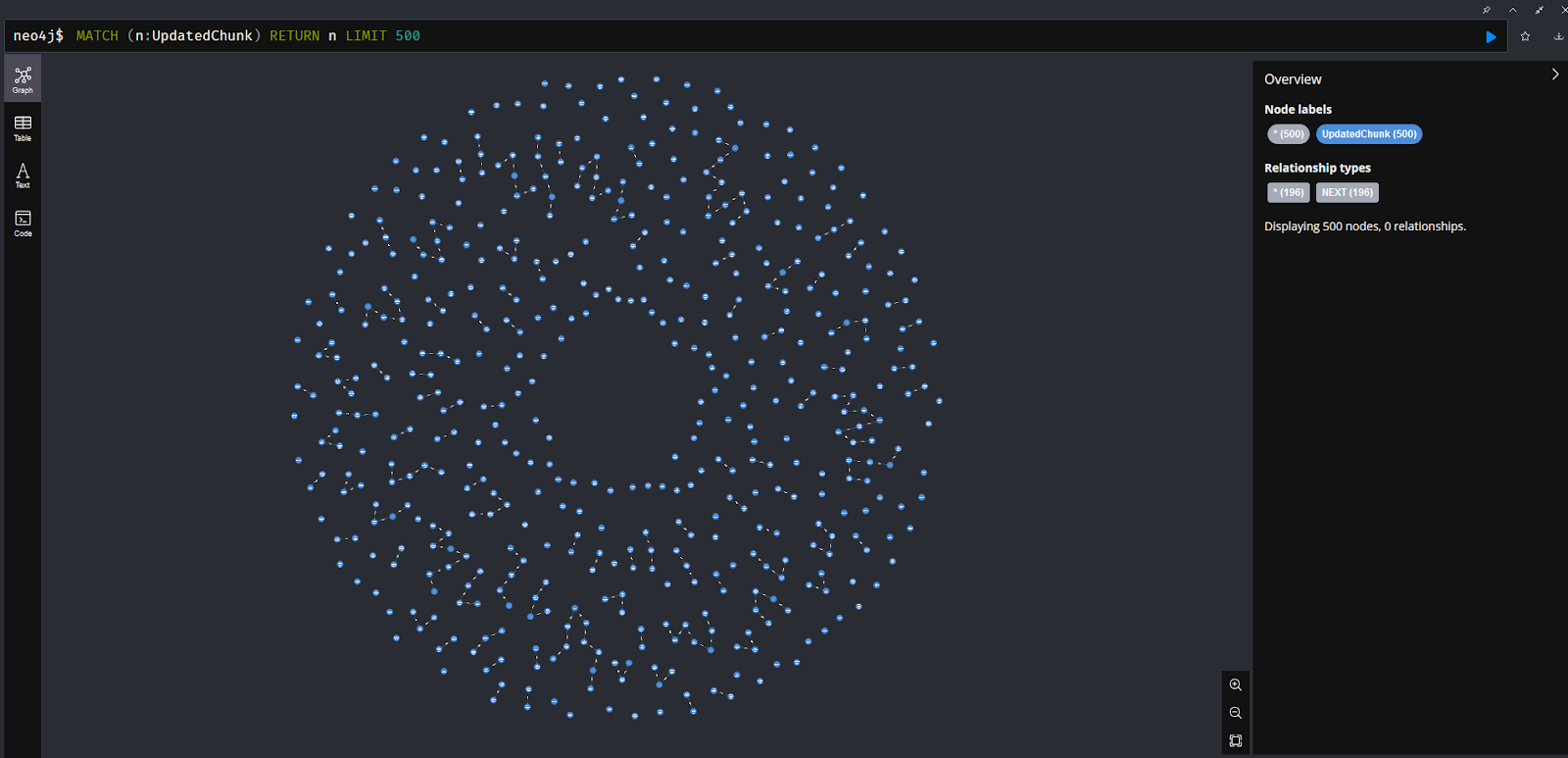

This process has already been done for all our existing data. For this project, it was all the data from the BC Acts and Regulations. The data was chunked into a predetermined size and used to populate our database alongside the embeddings that represent each chunk. In this case, we used Neo4j, a graph database that inherently provides a method of vector searching.

This is what this method looks like in Neo4j:

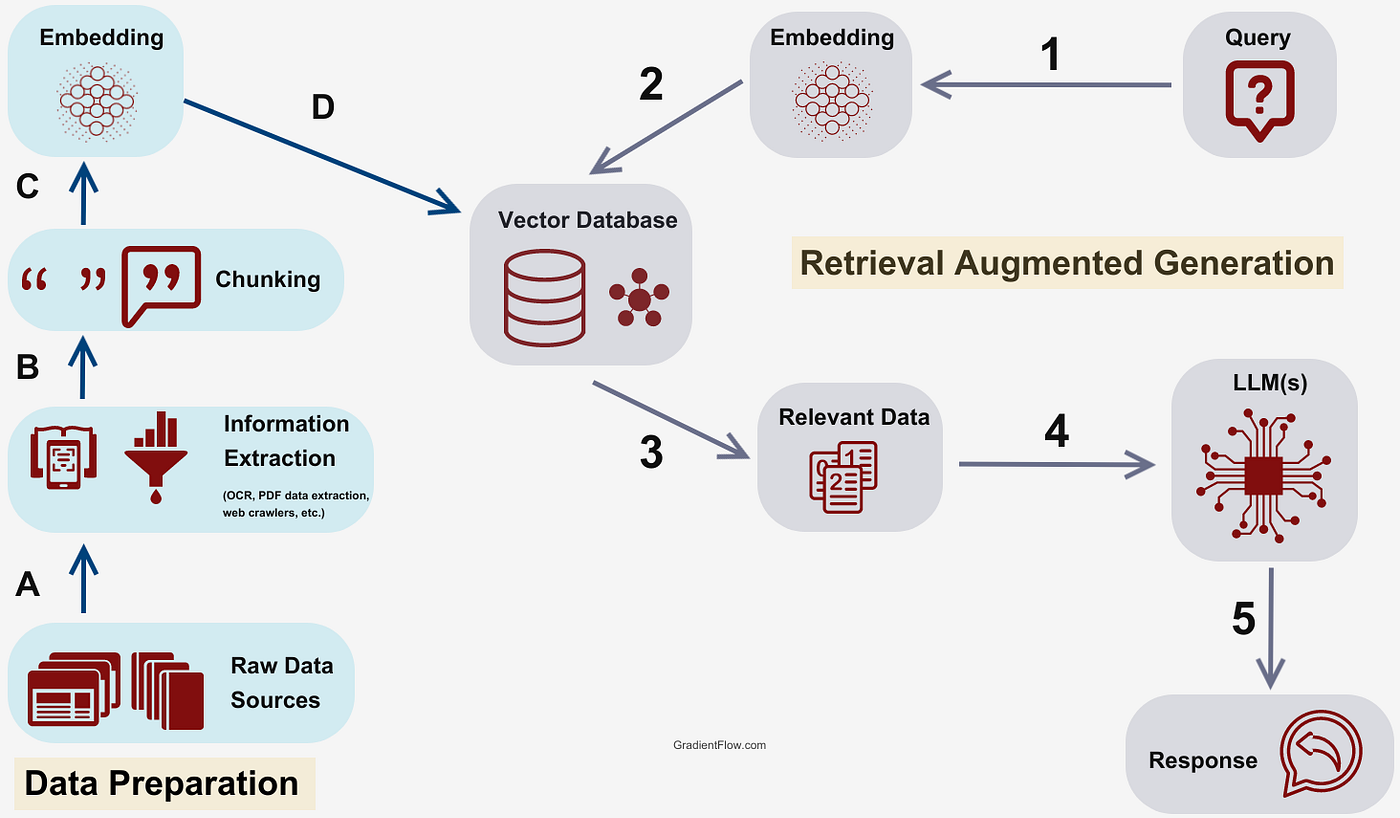

If you're familiar with vectors, you're probably used to thinking about them in two or three dimensions. The model we used to encode operates in 384 dimensions, well beyond something we can humanly comprehend. The final result is a matrix with dimensions of 256 by 384. The database can compare these vectors in a flash. It compares the vector encodings of the incoming query with all the vector encodings of the chunked data and returns the results with the closest similarity. You'll also hear this referred to as a cosine similarity search. This graphic from AirByte shows the process pretty well:

Now the database has returned the closest matches. In terms of semantic meaning, these should be the most relevant, but it's not a perfect science. We limit the number of nodes returned to 10 because the LLM has a limited context size. In this case, we were using a Mistral model with two-billion parameters, but the actual input limit is quite small. We actually need to feed the model with a structured prompt. This prompt needs to include instructions about how it should behave, what the initial question was, what context it should use, and any limitations on the response it should give. The whole process looks like this, courtesy of Gradient Flow:

Its output should be the response the user wanted all along. Of course, while the vector similarity search is deterministic, the LLM's response isn't. There are definitely still times that it doesn't identify the most important parts of the context provided. We tried adding a cross-encoder step, where we use another attempt at comparing embeddings to sort the results by relevance, before sending the context to the LLM, but I'd say the results weren't notably better.

So, let's look at what indexing actually entails.

Atomic Indexing

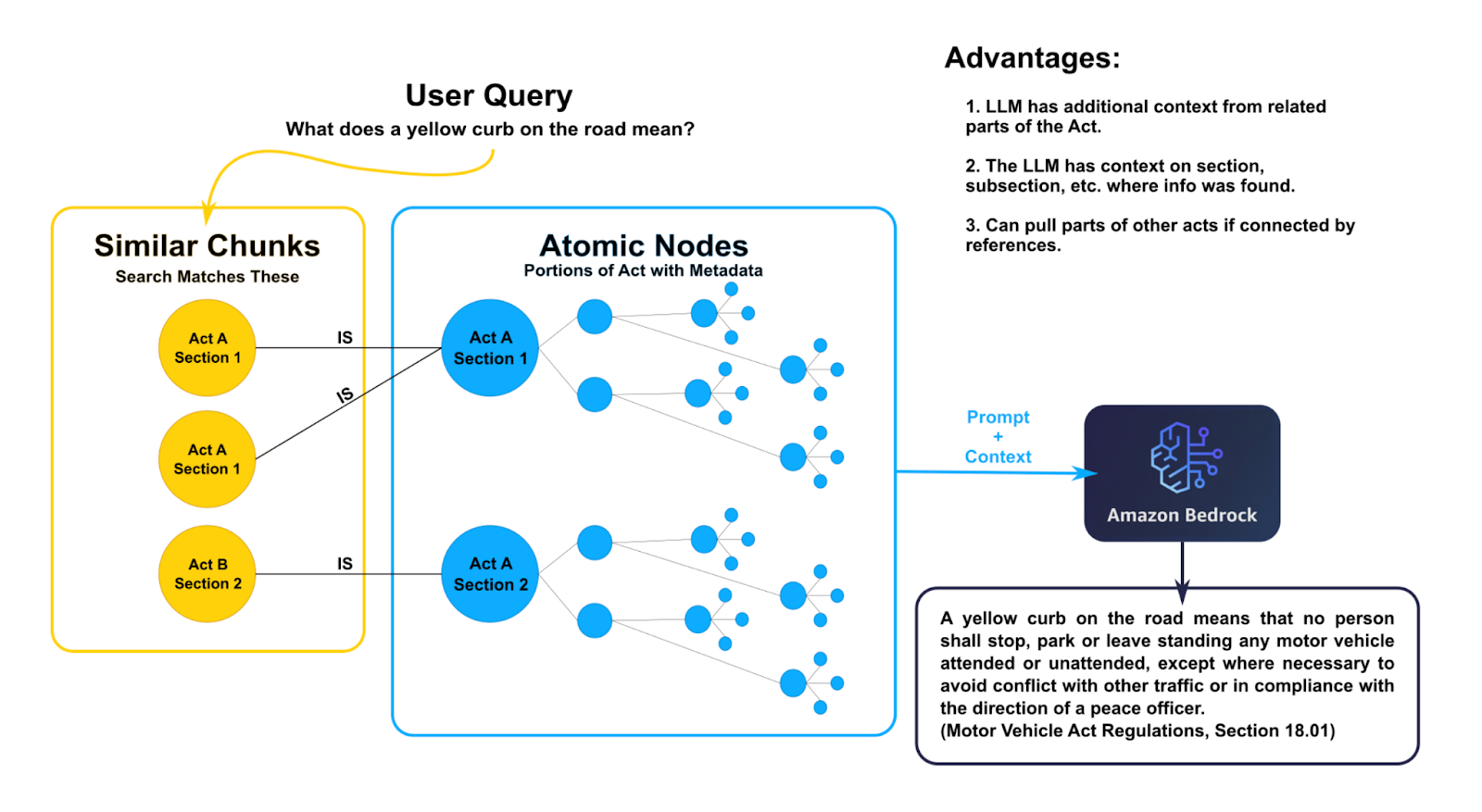

This was my first real project that I undertook on my own. The initial attempt at indexing the law data was done by breaking it into uniformly-sized chunks before creating embeddings. This is a very common way of doing this, but I found there were often incomplete portions of information that was matched, especially if one part of a law that matched the query relied on another part that didn't get returned. This meant the LLM was formulating responses based on incomplete information.

The other challenge was that there was no good way to connect relevant pieces of information. If you have a node of information that includes text from multiple subsections in a law, you only know where it came from based on metadata on the node, but it's not clear what its relationship is with other pieces of the law. It gets even harder when there's a text reference. If it references section 3, how can you be sure it's the section in this document and not one in another document? The answer that seems most apparent when just looking at the laws is to find the closest one, but if the nodes aren't spatially connected, how do you do that?

My plan was to re-index the law data down to its smallest components, hence the name that stuck: Atomic Indexing. Every part of the law would be represented by a different type of node. For example, an Act node will have several Section nodes, which in turn will have Subsection nodes, Paragraph nodes, and so on. All of the sudden, we can treat this indexed data not as a random collection of unconnected nodes, but as a graph structure where all nodes are connected via edges to their relevant data. The end result is actually very beautiful.

Here's what this approach looks like in Neo4j. This is just a small subset of the data, but it sort of reminds me of how mycelium spreads.

A bit of coding later and this data was indexed. Each Act and Regulation had its own graph, but there was a new problem. Because some nodes contained a very small amount of information, it actually resulted in poorer context for the LLM. In the chunked method, it would at least return some context around the matching data. This method cut out that excess, but that's something the LLM actually needs to formulate good responses.

The answer was in a hybrid approach. Fortunately, the original chunked data had the document name and section number in metadata. Programmatically, I was able to connect the chunks with the Section nodes in the Atomic Indexing data. When we do the vector similarity search, it matches with the chunked nodes, but traversing the edges in our graph allows us to pull larger swaths of information from the atomic nodes.

The real benefit here is that we can ask very specific questions of the LLM if we include the node metadata in the context. For example, we could ask a semantic question and request that it cites where each piece of information came from. This actually worked really well in practice. Additionally, if you gave the AI the chance to search the database with standard queries, you could ask specifically for a summary of the Motor Vehicle Act, Section 3, and it could pull all that as context.

You can see some of my test code for this here.

Community Clustering

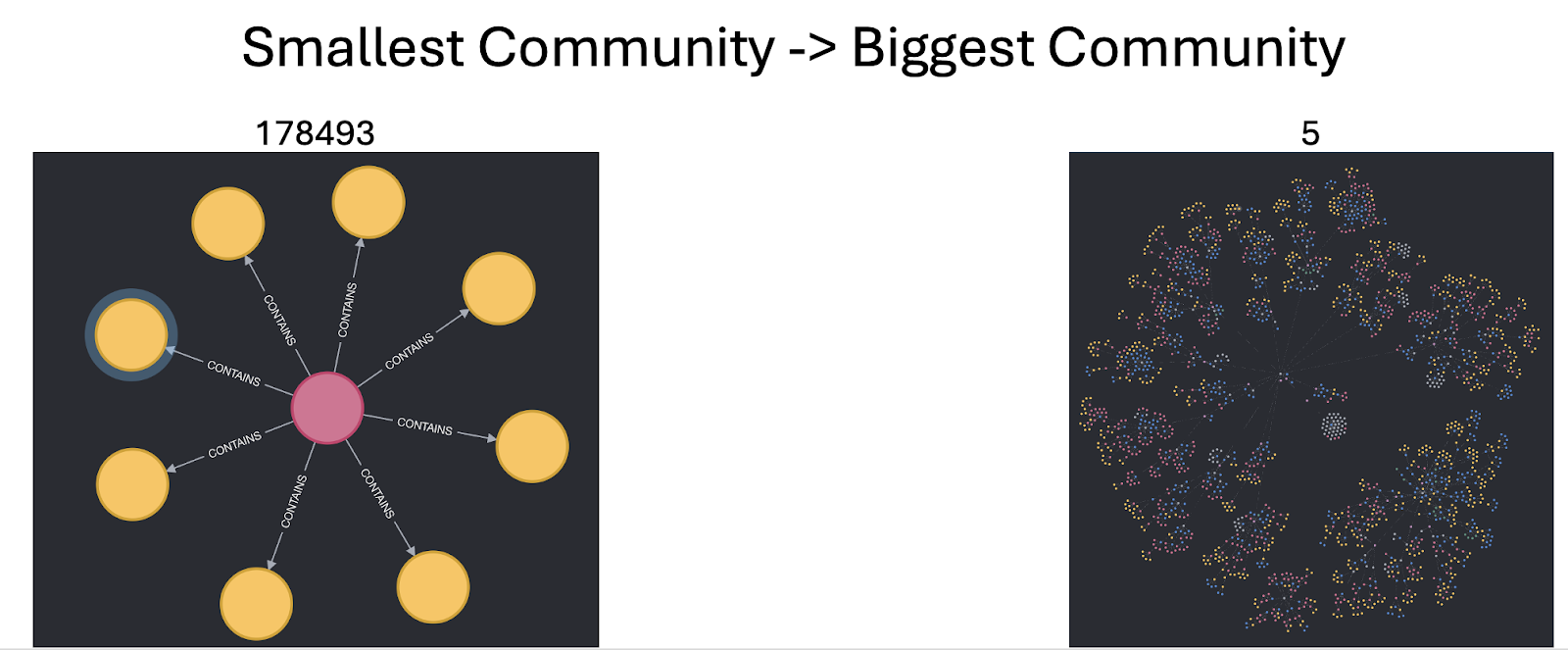

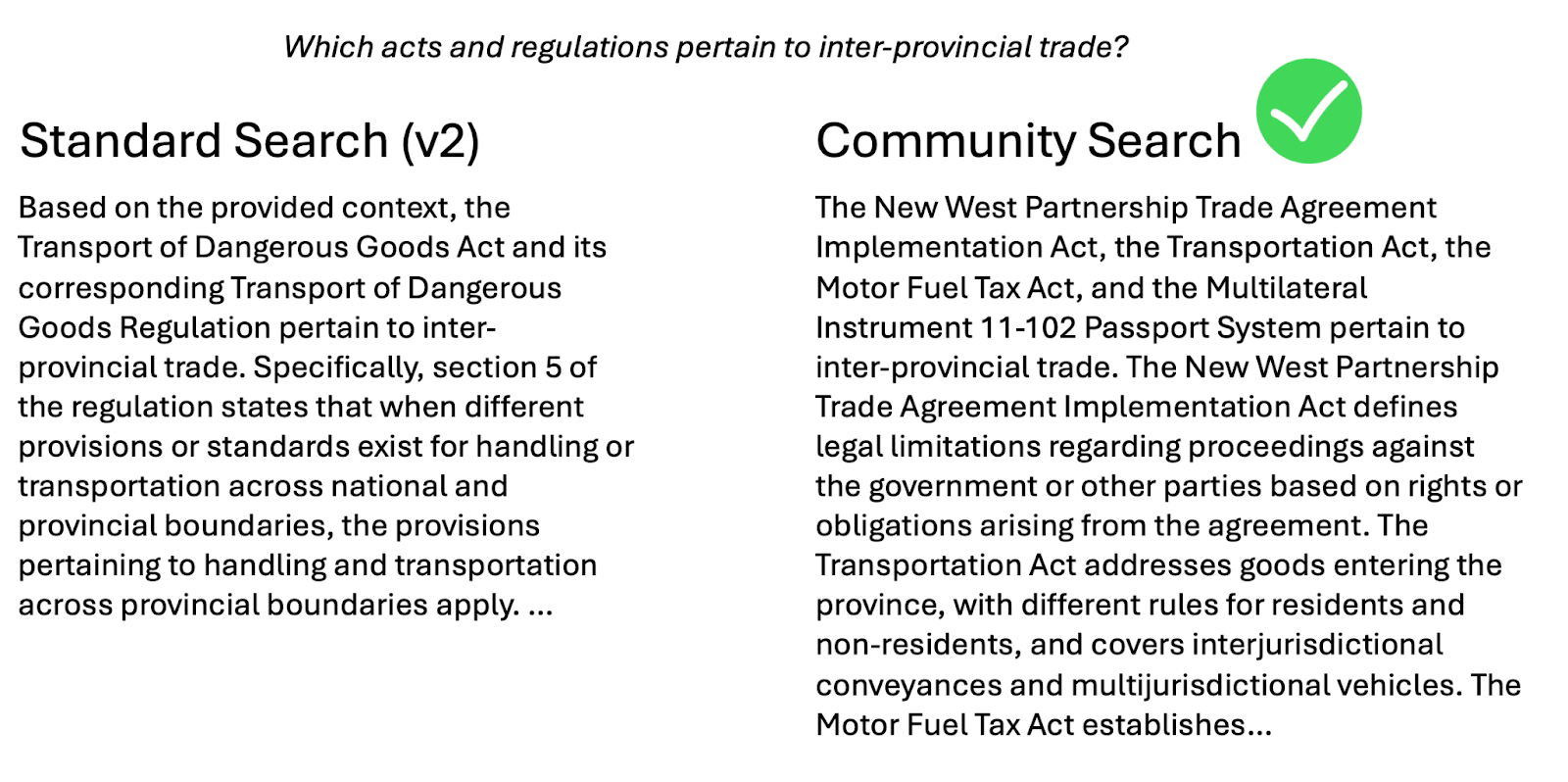

This was an attempt to imitate the global search option you might see in other enterprise services, like Azure. While the vector similarity search works well to find small pieces of data, it often can't return the right pieces of data to make a big-picture context. For example, if you just wanted a summary of what the Immigration Act entails, you either need to return all the nodes for that Act, or you could pre-summarize based on their existing connections.

A node with many edges to other nodes is more strongly connected than one that maybe only has one edge. By grouping nodes together based on the strength of these connections, we can create what's known as a community of nodes. These nodes should all contain related information.

So we can start to create communities, but there is one issue: the only edges are within Acts or Regulations at this point. The quickest fix is to connect any Regulations to their corresponding Acts, but there's still the problem of references within the text. Sometimes they refer to something in the same document, but sometimes they refer to other documents. I tried using an AI to detect this, but the results were mixed. Even with some fine tuning to try and have it recognise the references, it was too unreliable and would sometimes hallucinate the results. In the end, a robust series of regex seemed to work best, and it picked up about 90% of the references.

There are a lot of different algorithms to detect communities. It's a common problem in the world of graph theory. In our case, I used the Leiden algorithm. It wasn't the perfect approach, but it allowed us to ignore the directionality of our existing graph, and it was one of the built-in options in Neo4j. It's also incredibly fast.

Once the communities are created, Community nodes can then be made with LLM-generated summaries of each community's content. Of course, this still has to be indexed properly with embeddings, but then they are searchable just like all the other data. The challenge of context size is back again. We can't just feed data from an entire community to the LLM. To get around this, we can summarize in steps instead, creating summaries of summaries until it's boiled down to just the key information.

In comparison to GraphRAG on Azure, this was a big step up for us. Microsoft's solution had a fatal flaw: it was too quick to lump text items together as the same thing. For example, it would find the term “section 3” and create a node for that term. It then connects any node with instances of that term, but there's a problem there. Section 3 in one part of the law is most often not the same piece of law as referenced in other documents. There are hundreds of section 3s, but it treated them all the same. When your users prize accuracy, this is an immediate no-go. Here's one example of a question answered by the semantic search (Standard, here) and the community search.

Check out some of my work on this here, as part of the Atomic Indexing.

Agentic Chat & MCP

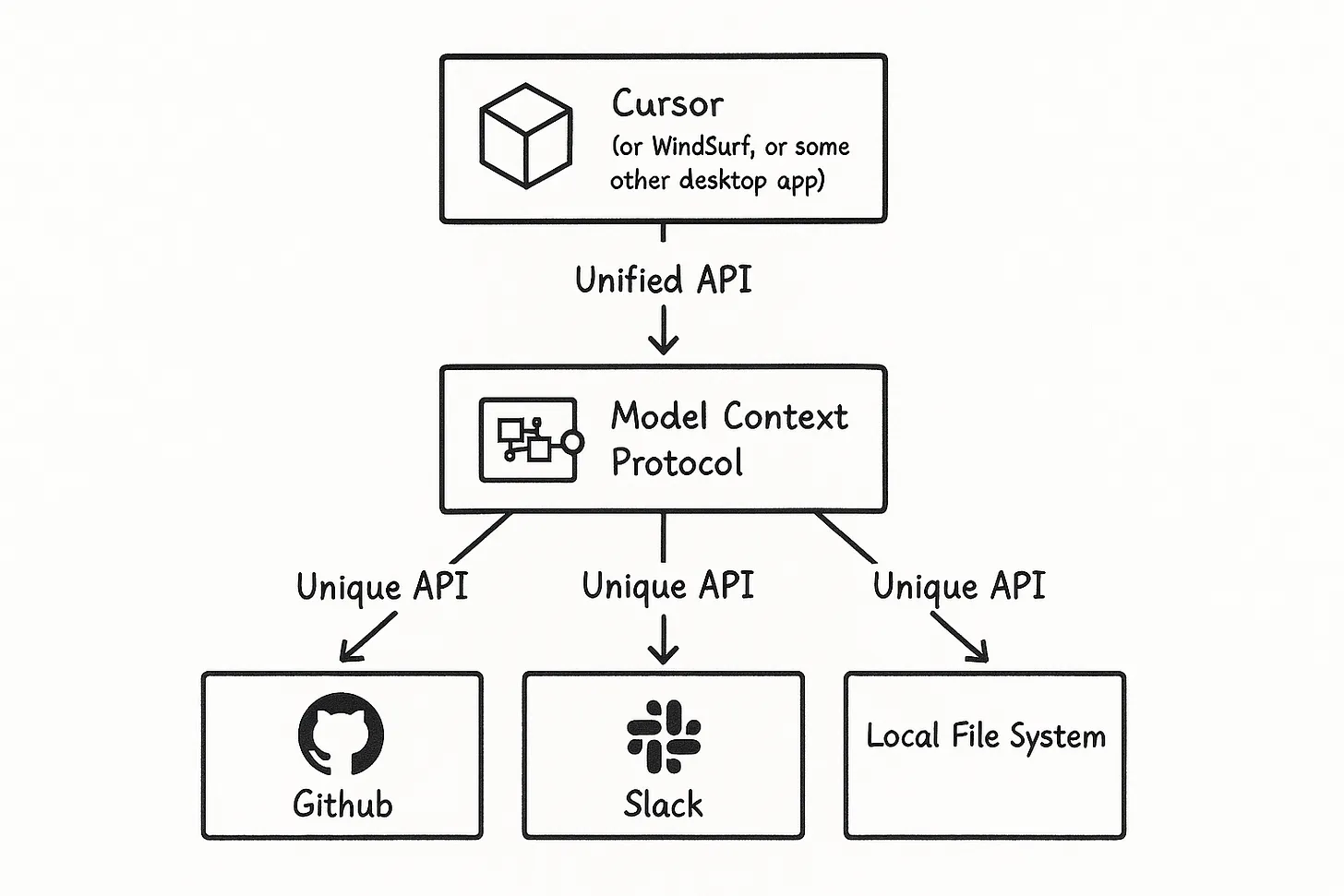

This was actually a fun venture where I got to focus on application design and not just prototyping. Model-Context Protocol (MCP) was just coming out as the next big thing. We had to look into it and see what kind of benefit it might offer. At the same time, we had been pushed off of using Claude Sonnet 3.5 as our premium non-local model, so we looked to Azure's offering they had finally got around to giving us. It was a direct endpoint to a GPT model, and it accepted MCP.

Now, MCP isn't as revolutionary as it sounds. In the end, it's really just a standardization for how an API presents a list of tools and other features that an AI can utilize. In our case, I wanted one that would present the AI with tools that could access our database in a few different ways. It needed to offer the usual semantic search but also an explicit search where the AI could decide the best query to run. Addy Osmani put together this diagram below that I think explains it very well. MCP is the extra layer here that makes your list of tools hypothetically work with any AI that supports tool calling.

Now, the MCP protocol is widely available. We used Python, so FastMCP was a very convenient method of getting this test ready quickly. You define each tool as a function, then the server essentially presents an endpoint that describes the tools available. When presented with these tools, the AI makes its best guess at which ones are actually necessary. If the tool description says it requires certain arguments, then it provides those, all in a structured format. Then it's up to your application code to actually run the tools and return the results to the AI. The pattern is basically a loop. The AI can continue to call tools until it's satisfied with the context.

If you're thinking that it sounds dangerous to give an AI access to run queries against the database, you're right. There's no way you should do this without some additional protections. In our case, I created software checks that hopefully catch all the common key words that would suggest a write or delete operation was attempted. In a real application, I'd hope whatever user the application uses to access the database only has read permissions as well.

As a side note, I found working with the Azure endpoint really easy. I had to make a chat loop mechanism that handled Azure's response, but even without any good documentation it was very self-explanatory. It will return its decision, indicating if there was an error, if it wants tool calls, or if it sees the process as complete and ready to return to the user. I would definitely use it again.

It was a good experiment that I think opens the doors to a lot of AI integration opportunities. It showed that it doesn't have to be 100% AI controlled, but a hybrid of human-constructed tools and AI decision making instead.

See some of this experimentation here.

Fine-tuning Gemma

On the back of this MCP and agentic flow testing, I wanted to know that we didn't have to rely on a big service like Azure to utilize it properly. Big models like GPT-4 just weren't able to run on our limited hardware. If we utilized compute from the larger government servers, maybe, but that's a big dedication to ask of them.

Instead, I hoped to train a smaller model, a Gemma 2-billion parameter model, to handle that same decision making, then it could simply pass the gathered context to our other small Mistral model.

The biggest hurdle was actually having adequate data to fine-tune a model. I had that problem before on other fine-tuning tasks. Having someone sit down and manually create data was a pain, and I could never create enough to make an impact. This time, I leaned on Azure. Using our access to the GPT-4 model, I was able to generate 5000 examples of how GPT-4 would choose our tools. I selected a real chunk of data from the database at random, the model created a question to ask about that, then it identified which tools it would use to gather context.

By collecting this output, I could then feed the Gemma model with pairs of question-tools as examples. Pytorch, a common AI library, could then be used to fine-tune the model's results. I started with the completely untuned version, but by the end of training, I'd say it was about as good as the GPT-4 model. The nice thing about this usage is that there's no penalty for getting it wrong. It's really just less efficient if it gets context it doesn't need or less accurate if it's missing context.

It wasn't a huge task, but it showed we could use bigger models to prepare our own fine-tuned models. This saves costs in the long run, and I think it set us up for more fine-tuning tasks in the future.

Check out this test here, as part of the Agentic Workflow.

Hyper-personalization

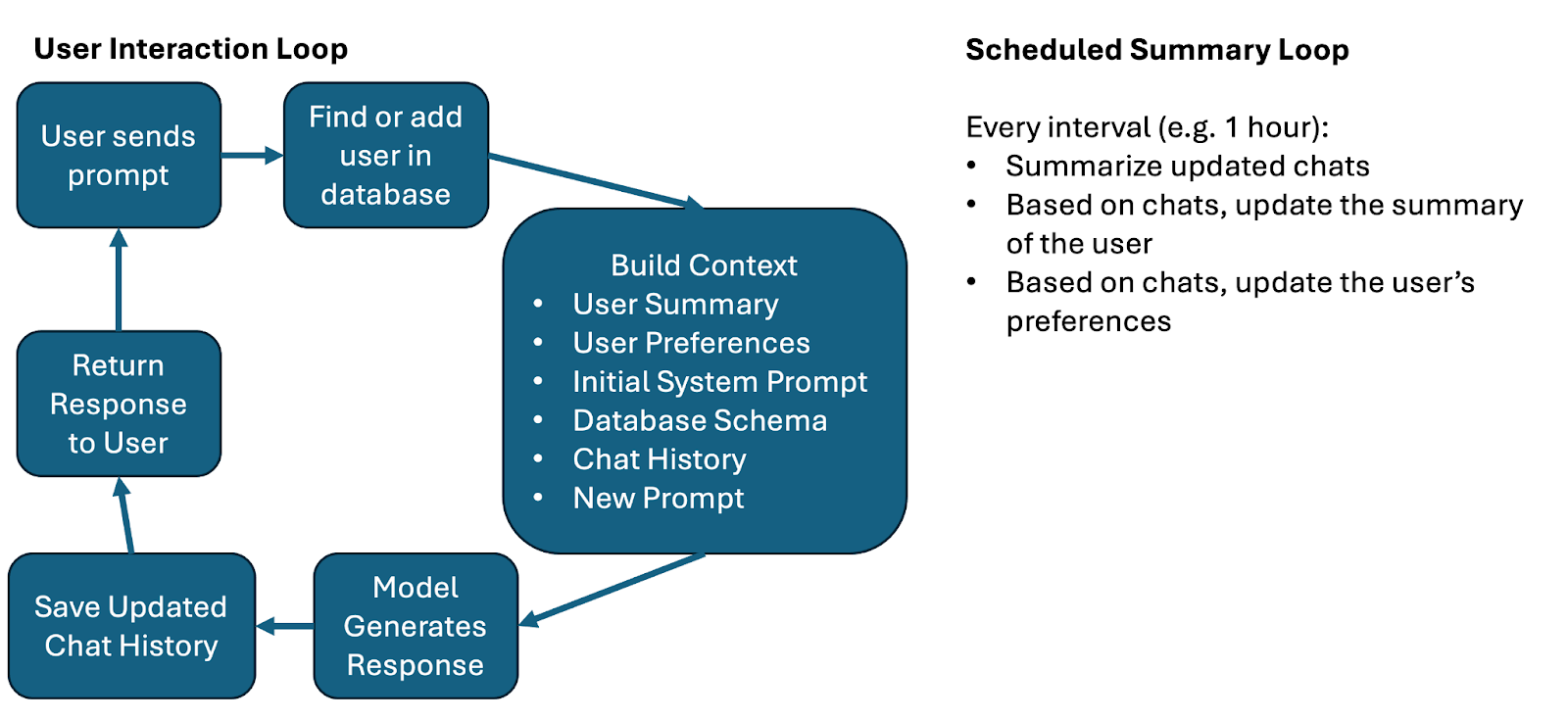

This was the final piece of work I took on before this experiment ended. It's a feature you see in pretty much all major LLM offerings these days. Users expect that a chat's history is used as context in future prompts. In some cases, there's even cross-pollination between chats. How could I replicate this?

The first step was to collect data from each chat. We weren't storing user data before, but now when a user logged in, we had to be able to track their usage and record their conversations. This part isn't too hard. I described this as the chat chain. It's a chain of events between the user and the assistant. By storing this chat chain in the database, we can pull it with every new prompt and use it as context for the LLM.

It doesn't end there, however. With this new data, I was able to schedule routine summarizations of chats. If additional information enters the chat chain, it gets re-summarized, and this summary can be used anywhere. In this case, I wanted to use it to generate an additional summary about the user themself. This is all additional context for the LLM. It now knows about the user: what topics they frequent, what mannerisms they use, what analogies they might find most fitting.

There's also a system that looks for user requests to the LLM. If I, as a user, ask that the LLM only use simple language or only use metric measurements, it should remember that. This information could be pulled from chat histories and saved in the user's preferences as a JSON object.

This was a really fun activity, because I then had to test it. One test I'll highlight actually set off Azure's safeguard countermeasures. I had asked it to only speak to me in Italian, but then later I pleaded with it to speak in English no matter what other instructions it received. Apparently that's enough to get an alert from Microsoft. It's good to know it's working!

You can see some of these tests here.

Next Steps

This project has now ended, but the journey isn't over. There's a whole new branch for AI Adoption, and I'm part of it now. It's time to take our experiments onto bigger things and create products that benefit the rest of the public service and citizens.