Advent of Code 2024

2025-01-03

Another year, another Advent of Code, a free series of online code challenges that release every December.

My first year was in 2022 (see that post), and I enjoyed it so much that I decided to keep going with it. Last year I attempted the year in C#, but as the holidays get underway it gets harder to keep up with the challenge, and I didn't end up finishing.

This year, I prepared myself by going back to a previous year and trying out some early problems. The first few days of each year tend to be a bit on the easier side. This also gave me a chance to try out Rust. We had been talking about it at work, and the AoC challenges are nice environments to experiment with new languages. In contrast, I planned to do 2024 in Dart. I have a Dart and Flutter course lined up that I'm hoping will help me get some personal mobile projects off the ground, so this seemed like a good time to jump in.

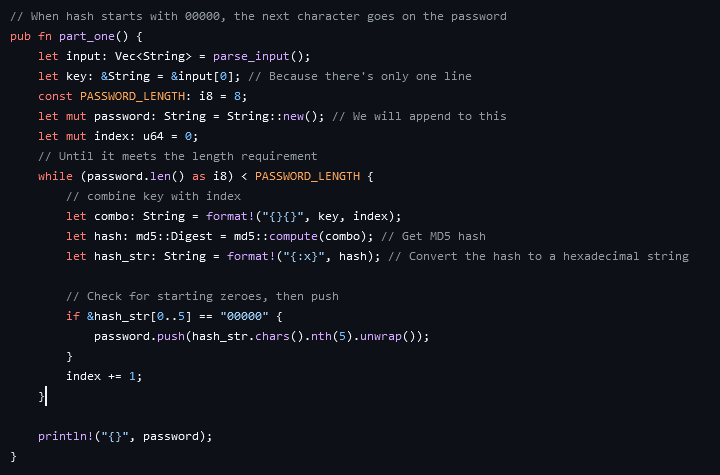

Of course, having dipped my toes into each at this point, I need to make this comparison. Rust has a lot of internet support. Everywhere you go, someone feels the need to suggest it. Having done so, I'm not the biggest fan. There were just a lot of simple actions that required seemingly arbitrary steps (unwrap I'm looking at you). Sure, if I wanted finer control over memory allocation, it offers that, but I rarely do that kind of work, and if I did, I'd probably look back to C++.

On the other hand, Dart felt like a familiar friend. I would liken it to some crossbreed of JavaScript and C#. When I wanted a method from a data structure, like sorting an array or getting entries from a map, it was second nature to type something that Dart expected. No additional steps, no issues. Because of all this, I'm definitely more likely to pick Dart again in the future.

The Actual Event

There are 25 days, and each day has Part 1, which is usually a gentle introduction to some problem that the elves are having this Christmas, and Part 2, which ramps up the complexity and scale or completely changes your understanding of the problem. If you were diligent and lucky with Part 1, sometimes it will also work for Part 2.

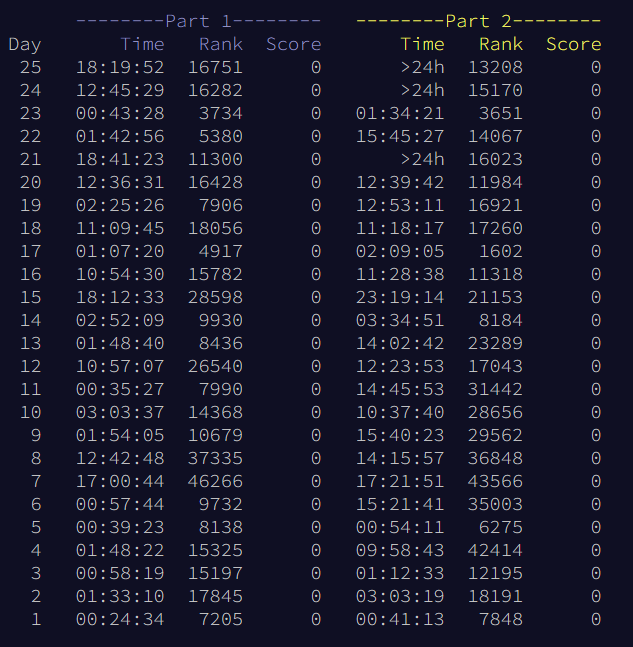

Compared to last year, I actually felt like this year went way smoother. In 2022, the best rank I got was 10,854 on Part 2 of Day 25, which means I was the 10,854th person to complete that part. In 2023, the holidays got in the way a bit, and I didn't manage to finish nor beat my record. This year, I managed to get a rank of 3,651 without any outside assistance. I was very excited about that one. My other goal was to complete both parts of each day within the 24 hour mark, at which point it stops counting your time and just marks it as “>24hrs”. Until Day 21 (the day I left for the holidays), I managed to keep that up, and only that day, Day 24, and of course Day 25 (because it relies on the other days) took over that 24 hour mark.

This was honestly a little more stress than I needed during the month. Having a counter tick down every day is just one more thing that I probably didn't need, and the challenges releasing at 9pm every night didn't make it easier to get done, as I either started then and stayed up a bit late or lost a lot of time until I could work on it the next day. I don't think I'll put that pressure on myself if I do this again next year.

There's no time to talk about every day, so I'd just like to highlight a few of the things I think went well and those other things that didn't.

What Went Well

There's often a trap in many of these problems where they can be represented as 2D arrays. These grid problems don't often have something in each element, so it's not very efficient to build out the whole thing, especially if the grid is huge. I didn't fall for that once this year, instead opting to use Map or Set objects to hold coordinates where needed. There's a good example of this in Day 08.

On the topic of grids, they are actually pretty much just very consistent graphs, and I've been doing a graph algorithm course through Udemy lately. It came in handy. There were so many opportunities for breadth-first searches or Dijkstra's algorithms that having practiced it so much gave me the ability to just pound out the code without having to look it up this year. Day 18 has an example of this, but it's not my favourite solution in general.

Memoization, or caching, is when you store previously determined values for later use. This can result in higher memory usage, but it means avoiding a lot of computational time. It's another trick that many of the problems require when you get to Part 2. There are cases where you would otherwise have to calculate trillions of outcomes, many of them the same calculation. Memoization takes the time needed from years to milliseconds if done right. Day 21 might be the best example of this.

What Went Poorly

There was only one problem that required a more complex knowledge of bitwise operations apart from the usual single-operation ones. My brain just doesn't think in that way when it comes to manipulating numbers, and it made days like Day 17 really tough. I had to look and see what other people were doing with this one.

There's the claim on the site that all these problems can be solved by old hardware in only a matter of seconds if done correctly, but sometimes you have a working solution that just takes a little too long to work on a bigger scale. The smart thing to do is just to improve your solution, which maybe means a major rewrite or at least some evaluation of where it could be more efficient. Other times, it's more compelling to just let it run and brute force the answer. I'm happy to say there's only a day or two that I settled for the latter, but it's still not ideal to see it run for 10 seconds when you know it's possible in under one.

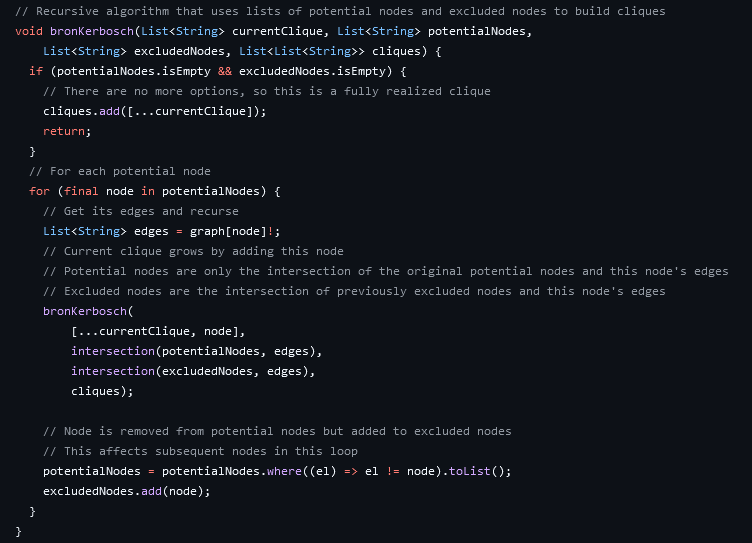

Day 24 really knocked me down. It was the last day that I managed to finish both parts on, and it involved a circuit design known as a Full Adder. I didn't know that when I started, but I did a lot of research. I still don't think I fully understand the purpose of the circuit, but it was enough to get some cases where I could identify where the circuit was incorrect, which was the goal of the puzzle. I had a solution that would brute force its way through a series of configurations, but it printed out four possible answers, one of which ended up being correct. It was not ideal, so afterwards I ended up looking to see how others had done it. There was a much smarter way where I could check the outputs to see which Full Adders had errors, identify the swap needed, then try again until the next error was found. It brought the solution time down from 30 seconds to maybe less than one second. That was one puzzle I was just glad to be done.

Conclusion

I'm glad I did this again, even though I haven't had much luck in getting other people involved. I feel like it would be more interesting with a group of people who I could discuss the solution with in person. I'll probably give it another go next year, but maybe not with the same zealotry as I did this year.

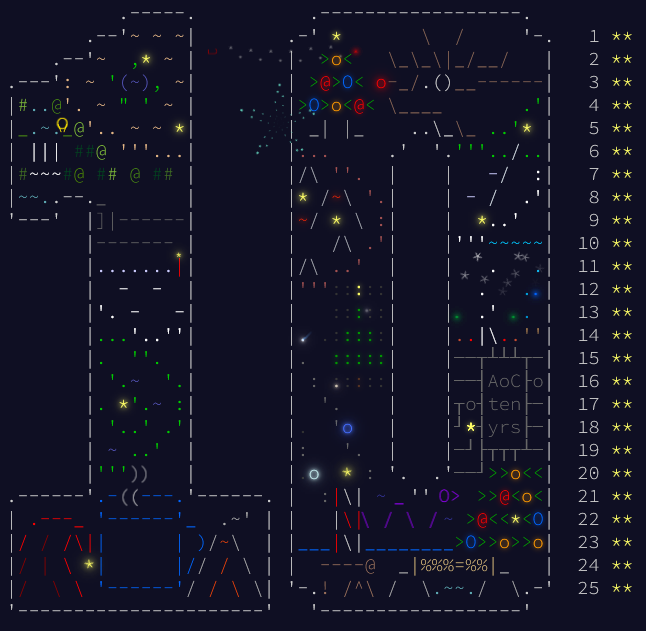

If you'd like to check out the solutions, see the 2024 folder from my Advent of Code repository. For now, here's the completed picture for this year's solutions, and thanks for reading.